This is a question that’s asked a lot on YouTube and on other social media sites by people who either are writing a book or people who want to write a book.

Everyone has a different answer to this question. At one extreme, some people say that you are only an author or a writer once you’re making a lot of money from books you’ve written. This is a very unpopular opinion, as it would mean that lots of people who are generally considered authors or writers by most other people would now lose the title – it would be a fairly useless definition. At the other end, some people say that you are a writer if you write. This definition is, in a literal sense, completely true, but also so broad as to possibly make the title ‘writer’ useless.

Now, I’ll start this post by saying that actually I really don’t mind how anyone else decides to use these terms – you want to call yourself a writer or an author? Go ahead – it doesn’t bother me. I’m not writing this post to try to suggest a ‘right’ definition for these terms – use whatever criteria you want.

The reason why I’m writing this post is because I had strict criteria that I used for myself – before I would call myself an ‘author’ – and it was very rewarding. And other people may also find it rewarding, so I thought I’d write it down in a blog post, in case anyone else wants to do it too.

(I’ll also say at this point that I’ve never really had any interest in the word ‘writer’ – I technically am a writer, but I’ve never used the word to describe myself. The word I’ve always fixated on is ‘author’ – the rest of this blog post is going to be about the word ‘author’, but it could equally apply to ‘writer’ if that’s the term you prefer.)

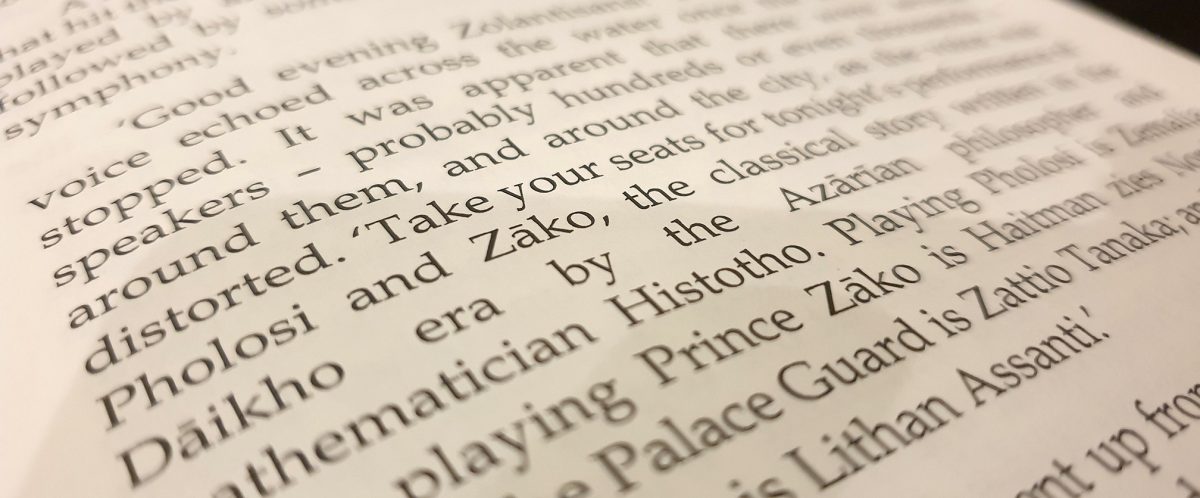

I only started referring to myself as an ‘author’ once I’d published my first fiction book (which was Zolantis back in 2018). I had been writing fiction for many years before that, but I only allowed myself to start using the term once I had published some of that fiction in my first book. There weren’t any criteria on what kind of book it had to be – it didn’t have to be a novel (in the end it was, but Zolantis wasn’t planned as a novel – it’s really more of a long novella). It didn’t have to sell loads of copies either – in fact I didn’t care if it didn’t sell any copies at all. It just had to be a book, and it had to be published.

Doing it this way was very motivating, because for the entire time before publishing Zolantis, I really wanted to finish a book, so that I could start using the title ‘author’. The desire to have a book of which I was the author, and to be able to start using the title ‘author’, gave me the drive to finish Zolantis. And then when I did finish it, not only did I have the reward of a book that I could hold in front of me that was mine, but I could also start using the title.

And this would be my advice to anyone else: if you wait until your first book is published before using these terms, it will drive you to finish that first book (and the first one is often the hardest one to finish).