I have always been tremendously jealous of the Welsh flag. It’s got a dragon on it – it looks fantastic.

The English flag, by comparison, is rather plain – a red cross on white. Plainness is generally quite a good thing in flag design – it means the flag is easily recognisable and easily reproducible. But still – who doesn’t want a dragon? Dragon flags look fantastic. The flag of Bhutan has a dragon on it, and it looks amazing. The flag of the Qing dynasty also had a dragon on it, and that looks even better – a truly outstanding flag design – much better than the current Chinese flag – they should consider going back to it.

Why can’t we have a dragon on our flag? Well the thing is … we could. The symbolism of the red dragon on the Welsh flag goes back to Arthurian legend. A red dragon and a white dragon are locked in combat, with the red dragon representing the native Britons (the Celts) – now the Welsh – and the white dragon representing the Anglo-Saxons – now the English. So a white dragon is a symbol of the English.

This is fairly well known – lots of people already know this, and lots of people have already had the idea of making a white dragon flag to represent the English. (I mean, you could argue the idea never went away from Anglo-Saxon times – the Kingdom of Wessex used a golden dragon as its symbol (still on the flag of Wessex today, though as a wyvern (the distinction being somewhat unimportant here)), and the flag of Somerset also features a dragon.) But the idea has not spread very far – partly I think just because of a lack of awareness of the symbol, but also because of a lack of good designs. A good design propagates on its own.

So for a while now I’ve thought it would be good to make some designs for an English White Dragon flag – an unofficial flag as an alternative to the St. George’s Cross.

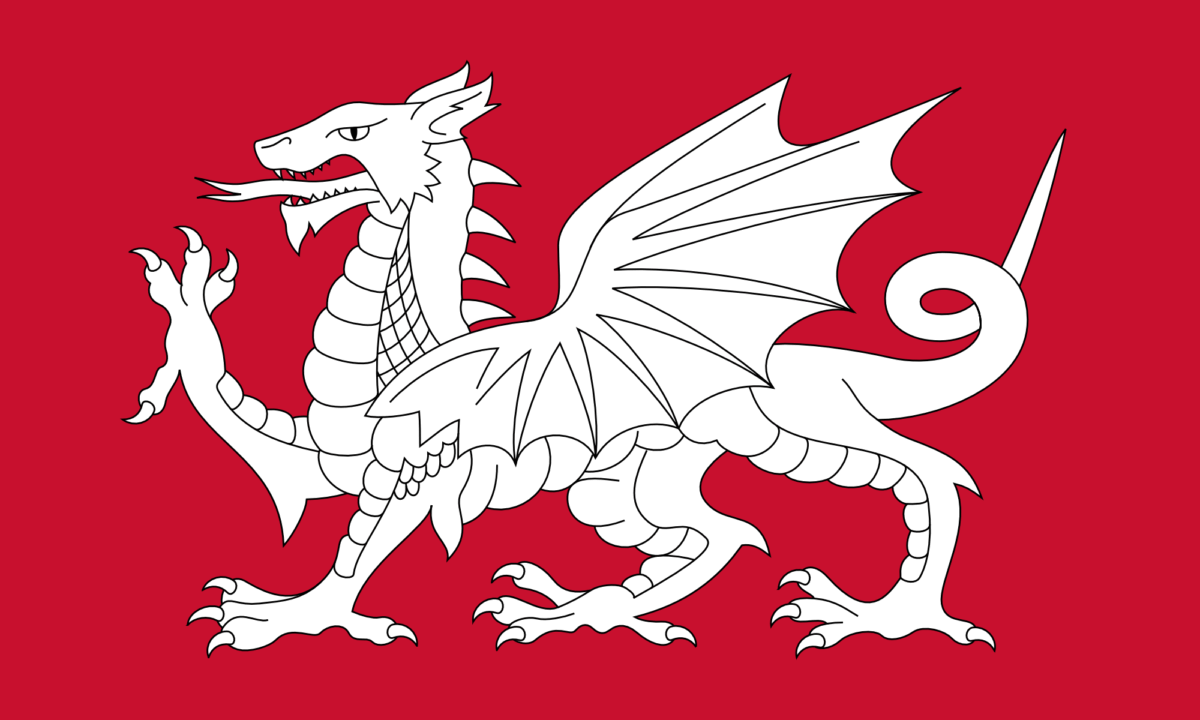

The simplest thing to do is just to change the colours on the Welsh flag, as shown below. (I am most certainly not the first person to do this – you can see that others have already done it just with a quick internet search.)

This is the exact same design as the Welsh flag – it just uses the red of the dragon from the Welsh flag as the background, and then the dragon itself is pure white. The design is incredibly striking – I think actually even more so than the Welsh flag.

This design also looks fantastic with a black background.

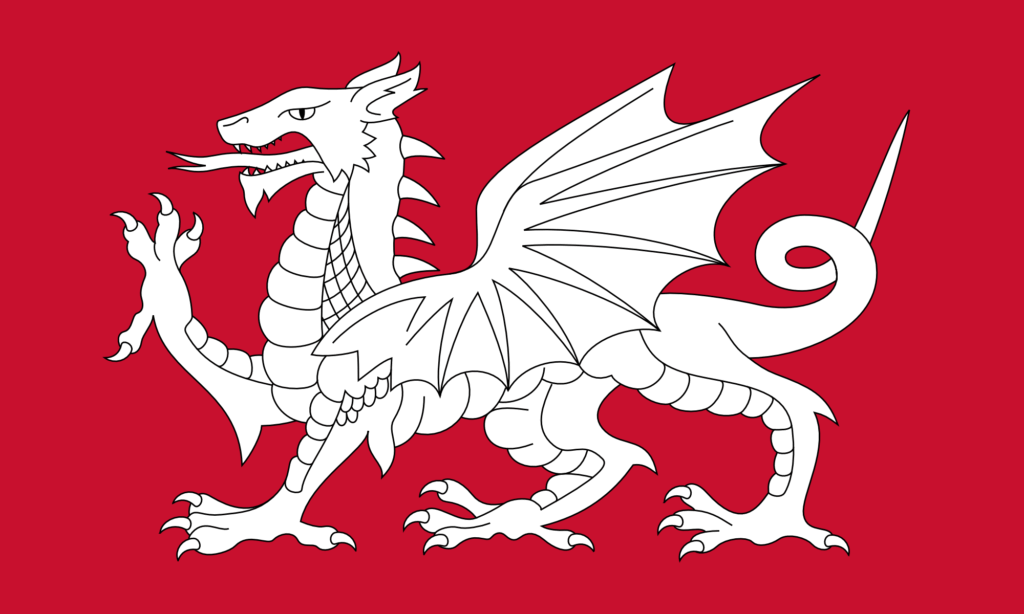

As with my design for a flag of Wiltshire (featuring a white horse), I find myself torn between different styles of illustration. The dragon on the Welsh flag is obviously very stylised – it’s not just a dragon, it’s a heraldic dragon. I particularly like heraldry and I quite like the heraldic style of illustration, but I do think there are some things that are a bit odd about the design here.

I have never liked what I call the ‘demon’s tail’ style of tail that the design above has. Almost every cartoon drawing of a demon has a tail like that. Personally I think it would look better if it were more naturalistic. That goes for the dragon’s tongue too.

I have also never liked the ‘nose horn’ of the dragon. This seems like a rather odd place to have a horn (that is, a forward-pointing one). In more naturalistic depictions of dragons – which are rather common nowadays thanks to CGI – you never see this. (It’s a remarkable thing that, with decades of stories and movies about dragons, we now have a very strong collective understanding of what a dragon is supposed to look like.)

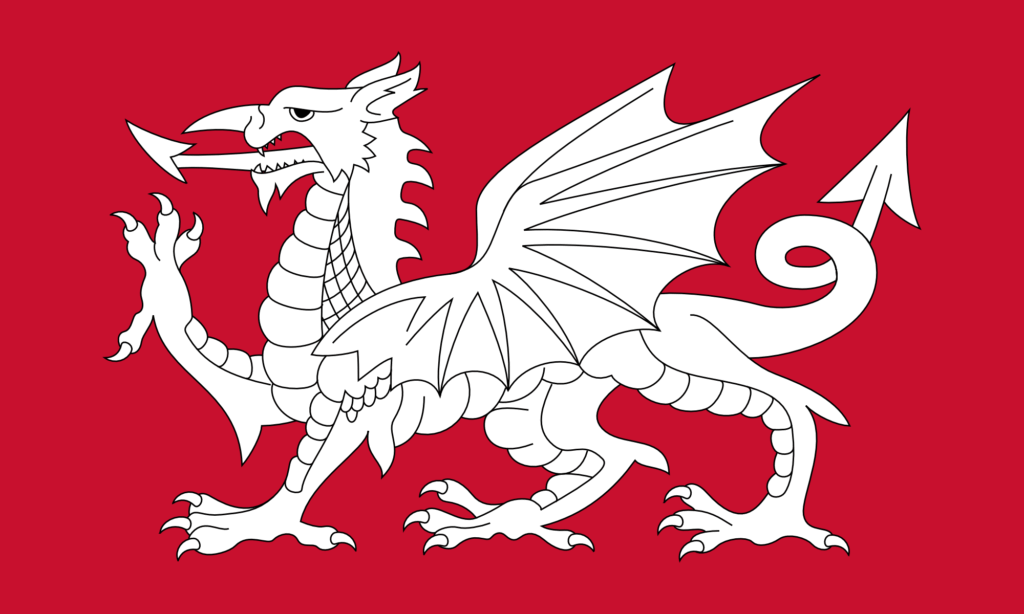

So I set about modifying the above design. The result is below.

As with my design for a white horse flag for Wiltshire, I found that there were so many things to agonise over while making this design.

I wanted to make some improvements to the design, but I also wanted to retain much of the style – the heraldic style – of the original design. Of course, here we’re not dealing with a purely mathematical design – we’re dealing with freeform paths that can be given any shape. Should this control point go here? Should I move it slightly? Is that a better curve? That looks good, but does it deviate from the style too much? I agonised for hours and hours over it. I am not really certain about most of it, but at some point you just have to decide that it’s done.

I have removed the ‘demon’s tail’. I have also changed the tongue. Now, I’ve given it a forked tongue – that’s sort of a bit of a problem because of course a forked tongue typically carries the symbolism of the snake and of deception. That’s not the intended meaning here, of course – the aim is just to be naturalistic.

I have removed the nose horn, and elongated the dragon’s face. I think this is a tremendous improvement – again, more naturalistic – but of course it does lose some of that heraldic style. I have changed the eye quite substantially – making it a bit meaner. The eye on the original design makes the dragon look a bit dopey. I have also adjusted its spines – and I think this is the only change that I’m completely sure of.

There are so many other things I could have changed (adding more spines along the tail, changing the wings to be a bit more anatomical, changing the ears to look a bit more reptilian, and so on), but of course that risks losing some of the style. As with my white horse flag for Wiltshire, I consider this to just be Version 1 – I may make other versions in future with more modifications. I would also like to make some versions that don’t use the heraldic design at all – and which use something a bit more ‘modern’, for lack of a better word.

So we English can have a dragon on our flag, and it looks rather good. As ever, I don’t suggest making this the official flag – it’s just nice to have as an unofficial one. I’ll be getting some of these made for myself.